Stacked pull requests are a powerful way to break down a large feature into smaller, meaningful subtasks. They let you keep moving forward on your work while reviewers can already start reviewing earlier parts of the change.

This workflow comes with many benefits:

- shorter-lived branches

- faster, more focused reviews

- reviewers staying closer to the work as it evolves

In this article, I’ll show you how to set up and manage stacked PRs using only plain Git commands—no additional tools required. Because it purely uses Git, you can implement stacked-PRs with any Git-based code review tool, such as GitHub, GitLab, or Bitbucket. This will be a hands-on, technical guide.

If you’d prefer a higher-level overview of the concepts, workflows, and available tools behind stacked PRs, check out my complete developer guide to stacked PRs.

Making Large Code Changes Reviewable with Stacked Pull Requests

Code reviews are hard but worth it. However, this equation changes when the code change becomes too large. Research confirms this: the more code to review, the less effective the review.

So, we should aim to review small code changes. But how?

That’s where stacked pull requests come in. It’s a technique I also teach in my code review workshops. It allows you to break code changes into smaller and more coherent pieces that live on their own branches. In return, reviewers have an easier time understanding the code change and therefore can give better feedback in a shorter time.

So, are you ready to learn how to do it with just Git? Let’s go!

Feature Branch Workflow vs. Stacked Pull Requests

To understand the value of stacked-PRs, let’s first look at the traditional feature-branch workflow and its limitations, and then contrast it with the stacked-branch workflow.

The Traditional Feature Branch Workflow

Imagine we’re working on a new feature: “adding and deleting items from a shopping cart.”

With a feature-branch workflow, we would branch off from the main branch to

implement this feature in isolation on its own dedicated branch.

This means we would commit all the changes related to this feature, probably

using multiple commits, on this branch.

After finishing, we open one pull request, and after approval merge

the feature branch back into the main branch.

This approach is common, but it has downsides for code reviews:

- By the time we open a pull request, the feature branch often contains hundreds of lines of changes (several hundred lines of code is typical). Research shows this is already past the point where reviews are most effective.

- The reviewer’s only option to break the review into smaller chunks is by following our commit history. But commits reflect the developer’s thought process, not necessarily coherent review units.

- Commits may contain partial work, reversals, or multiple iterations of the same idea—making them harder to review meaningfully. You will find a more detailed comparison to commit-based reviews at the end.

- Even if you open a WIP pull request to promote early review, the reviewer will see the code changing continually, making it hard to track progress or provide feedback.

The Stacked Pull Request Workflow

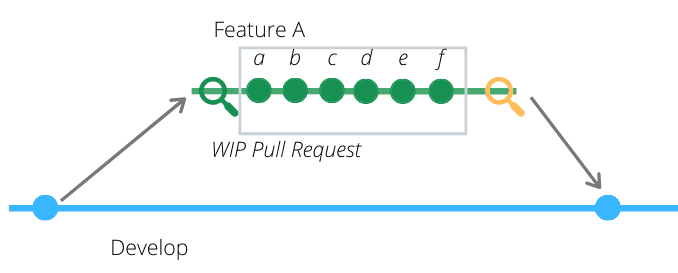

Instead of cramming everything into a single branch and PR, stacked pull requests let us break the feature into smaller, coherent units of work.

Here’s how it works:

- Each sub-task of the feature lives on its own branch.

- These branches are “stacked” on top of each other, so they build in sequence.

- Each branch becomes its own pull request—self-contained and reviewable.

What’s in it for reviewers?

- They review coherent work items, not arbitrary commits.

- They can provide feedback earlier, while the feature is still in progress.

- Reviews are faster, clearer, and closer to the actual work being done.

What’s in it for the developer and the team?

- You can keep working on the feature while earlier sub-tasks are already under review.

- Feedback comes in earlier, so you can adapt your approach before finishing the whole feature.

- Branches stay short-lived and easier to manage, reducing painful merges.

- The team builds a shared understanding of the feature as it evolves, instead of waiting until the end.

In short: stacked PRs turn one overwhelming, oversized review into a series of focused, high-quality reviews—helping both the author and the team.

Note that stacked pull requests are also useful during trunk-based development. Always if we have made many changes (more than, say, 400 lines of code) and we want to ease the burden on the reviewers.

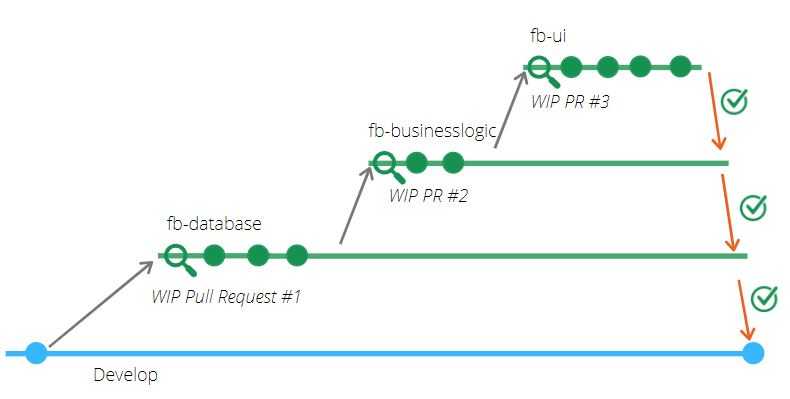

Let’s look at an example:

To split our features “adding and removing items from and to a shopping cart” into several work items, we can, for example, decide to go with an approach reflecting our system’s architecture.

Based on this decision, we start by making changes to the database layer. Then, we implement the business logic. And finally, we made the necessary changes to the UI.

Working with Stacked Pull Requests

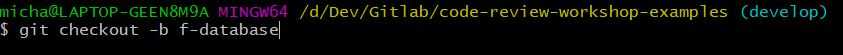

We begin our work by creating a feature branch for the first set of changes (let’s call it fb-database, for indicating that we work on this branch on the database layer for the feature).

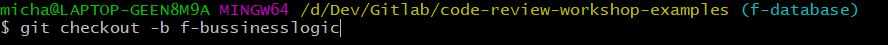

The git command we need for this is the git command to create a branch and check it out:

git checkout -b fb-databaseAs you can see from the screenshot, we are on the development branch before we create the *fb-database *branch. With this command, we now create the fb-database branch and also switch to it.

Then, we do our work and make several frequent commits until we reach a state where we think the database layer is in a good shape.

git add [somefilesthatchanged anotherfile yetanotherfile]Now, we push create a remote branch for fb-database and push our changes to it.

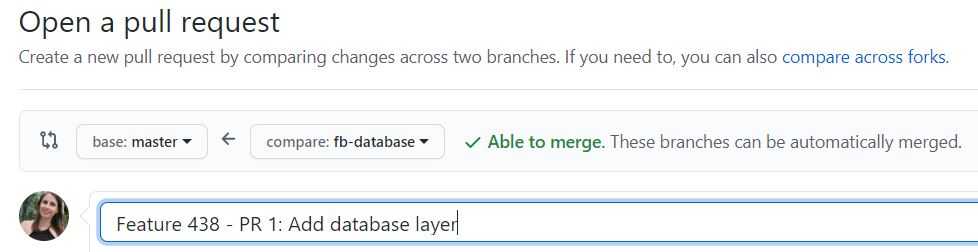

git push --set-upstream origin fb-databaseThen, we open a pull request just for those coherent database-changes.

Tip: An even better approach is to open a “Work in progress” pull request as soon as we create the branch. This way, our colleagues can follow our progress and get already a heads-up on our work.

Opening this pull request will look exactly like we would do for any pull request. We open a pull request comparing the code of branch fb-database to the code on the development branch.

This means that reviewers see the changes that we made in comparison to what happened in the development branch. Right now, there is no difference from the example before (except that there are fewer changes that happened in this pull request).

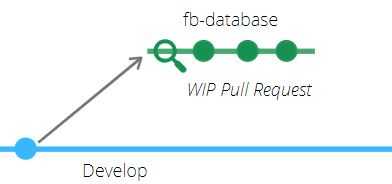

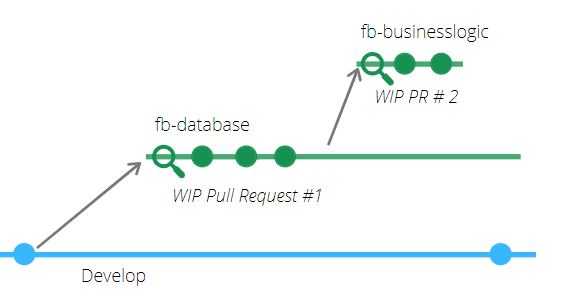

Creating the first stacked pull request

After we finish our first work item, we continue to work on the next work item for our feature. But instead of creating another feature branch based on the development branch, we create a branch that is based on the previous branch fb-database.

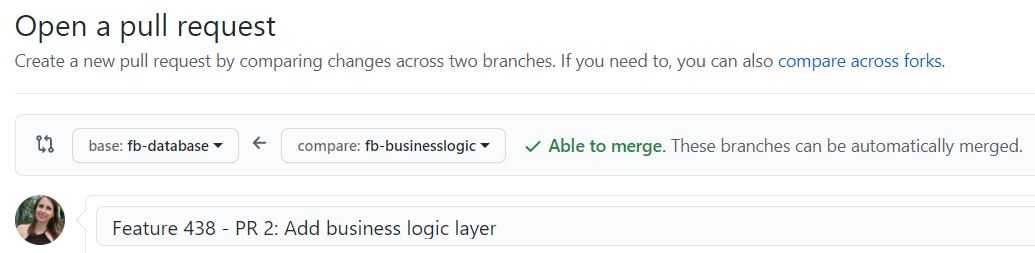

This means that all the changes we made on the branch fb-database, are already part of the code on this new feature branch, i.e. fb-businesslogic. It also means that we can continue working without being blocked, while others have the time to review our previous changes.

So, now, we are working on the changes to the business logic. And again, we open a pull request.

But now, this pull request isn’t based on the development branch. Instead, it is based on the branch fb-database.

This highlights that those changes are connected, and, as a result, the reviewer sees what changed between the fb-database and the fb-businesslogic branch.

Two stacked pull requests based on two consecutive branched (fb-database and fb-businesslogic)

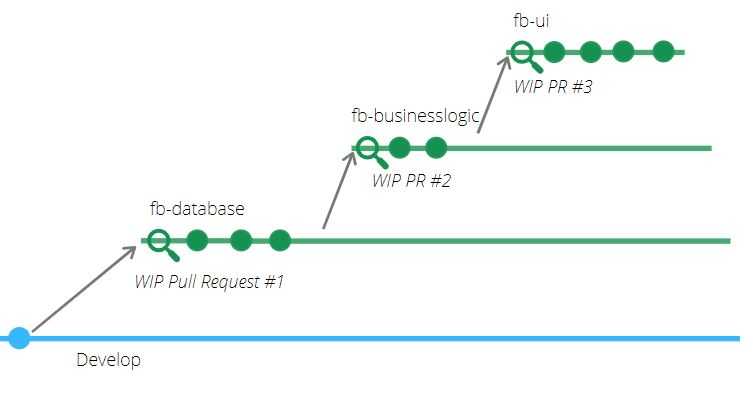

So, now we have implemented the UI changes. And once again, we branch off our previous feature branch (fb-businesslogic) to make those changes. We also open another pull request. Again, the PR points to the previous feature branch fb-businesslogic, instead of to the development branch.

Reviewing Stacked Pull Requests

So, how do we review those stacked pull requests?

The idea is that the reviewer starts with the pull request that was opened first. Then, they compare the code on the development branch with the code on the fb-database branch. These are also the first changes we made, and all other changes build upon those.

As a next step, the reviewer reviews the pull request containing the business logic. And finally, the reviewer reviews the pull request with the UI changes.

So the review direction is: fb-database -> fb-businesslogic -> fb-ui

Merging stacked Pull Requests

It’s important that reviewers do not merge code changes right after they review them. All stacked pull requests should be treated as Work In Progress pull requests until all stacked pull requests have been reviewed. This is because, we must start merging from the top, i.e., the last opened pull request. Doing otherwise will result in a state where we cannot merge our pull requests anymore.

In our example, once the reviewers reviewed all pull requests, we would merge the UI changes into the business logic changes.

Then, we merge the business logic changes into the database changes.

Finally, we merge the changes on the branch fb-database (which now comprises all changes) into the development branch.

So, our merge direction is: fb-ui -> fb-businesslogic -> fb- database

Handling Feedback and Keeping Branches in Sync

One drawback of the stacked pull request approach is the overhead of branches that we need to keep in sync.

For example, if a reviewer comments on our pull request handling with the database changes, we would make the requested changes on branch fb-database. But this means that we have to update and sync the fb-businesslogic and the fb-ui branch.

Let’s imagine we changed the fb-database branch after receiving some feedback. Now, we have to update the fb-businesslogic branch. We have at least two options to sync our branches:

- merge the two branches (resulting in 1 merge commit on branch

fb-businesslogic) - rebasing the

fb-businesslogicbranch on the changes of branchfb-database

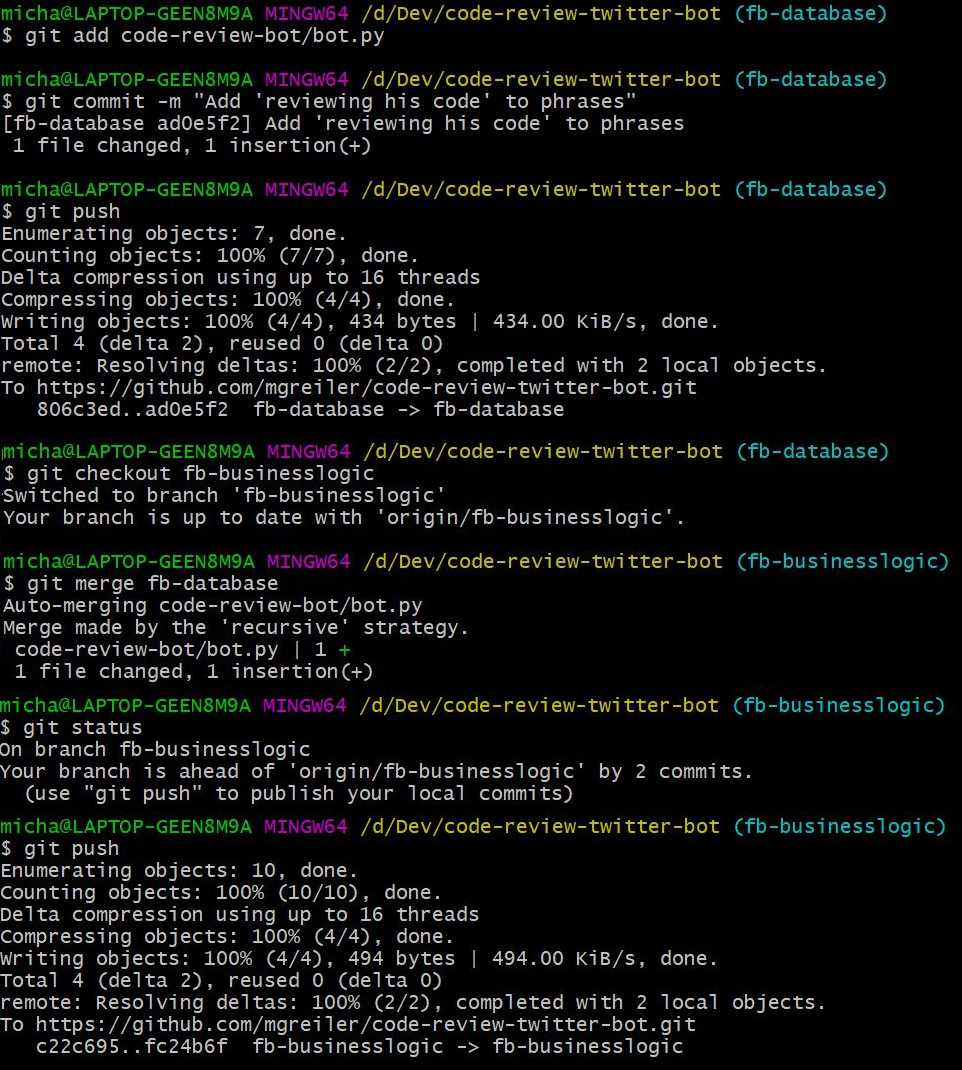

For both options, we first have to commit and push the changes to the fb-database branch. Then, we switch to the fb-businesslogic branch, which we want to “know” of the changes on fb-database.

git checkout fb-businesslogicSync using git merge:

On the fb-bussinesslogic branch, we use the merge command. Then, we push the merge commit to the remote fb-database branch so it’s visible in the pull request:

git merge fb-database

git pushThat’s it. fb-database and fb-businesslogic are in sync again. Now, we can do the same for fb-businesslogic and fb-ui. If we have merge conflicts, we have to resolve them first and then commit and push our changes.

Sync using the git rebase:

We can achieve a similar result by using the git rebase command. So, after we applied our changes to fb-database and switch to the branch fb-businesslogic, we use rebase to sync the changes.

If there is no merge conflict, we are fine. Otherwise, we have to resolve the merge conflict, and then continue the rebase using the command:

git rebase fb-database

[git rebase --continue] #optional if you have merge conflicts

git pushSummary

We looked at a technique called stacked pull requests that can help code reviewers understand larger code changes more easily. Stackedpull requests allow you to break up large code changes and to create dependent pull requests that improve the code review process for the reviewer.

Even if the process looks tedious or scary to you, I hope you take the time to try it out on your own. Only that way you can see whether this technique makes sense for you.

Maybe you need to do it a couple of times (2-3 pull requests) before you get the hang of it. But after that, you will be used to this workflow and have integrated it into your daily routine.

Now, before I let you go, let’s compare stacked pull requests to commit-based code reviews.

Comparison to commit-based code reviews

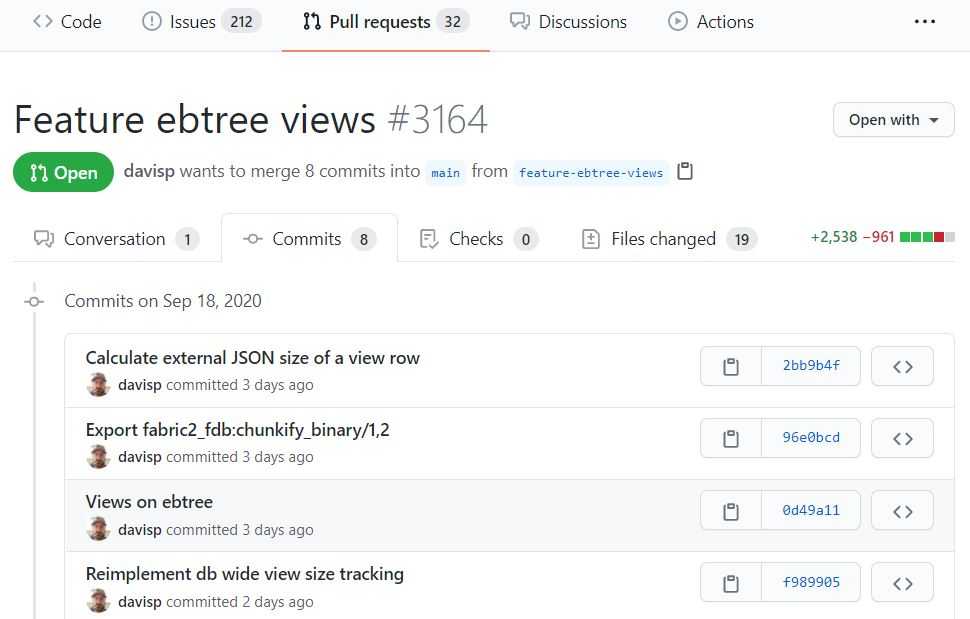

Most tools, such as GitHub, GitLab, and Bitbucket, provide you with a list of commits that happened within a pull request.

This is handy because reviewers can click on each of the commits and see what changed just within that commit.

In theory, reviewing the code changes based on commits means that the reviewers review smaller code changes and also that they can follow the progress of the developer.

The problem of commit-based reviews

Unfortunately, most of the time commits represent the developer’s progress and aren’t meant to ease the review. This means that in some cases, the reviewer might look at changes that are undone in a subsequent commit. Also, often commits tangle together several unrelated changes.

Some commits might not even compile, or they aren’t tested. Well, from experience, I can say that many developers have a hard time committing coherent, self-contained, and working commits. Commits often just represent progress points of the developer (like breakpoints before leaving the office or going for lunch).

Still, reviewing based on commits is frequently done because when we face large pull requests, we might clutch any straw we can get.

But even if our commits represent great reviewable items, like containing all the changes we made on each individual branch, commit-based reviews still have a main drawback to the stacked pull-request approach:

Reviewers cannot approve, reject, or ask for changes on the level of individual commits. Even commenting on code changes of a singular commit is handled differently from commenting on the whole pull request. Leaving comments on a particular commit might be hard to trace for the code author and reviewer, as they do not show up in the pull request discussion.

Related work

Well, I hope I have given you a good summary of the stacked pull request approach. This should serve as another mental model and workflow to deal with code reviews within GitHub, GitLab, or Bitbucket.

Finally, I want to highlight some other blog posts that discuss the topic of stacked pull requests:

Unfortunately, the post of Grayson Koonce is not available anymore. Yet, here is a short comparison to the approach I explained: Grayson highlights a workflow in which the developer isn’t working on several branches as they do the work.

Instead, they create the stacked pull requests in retrospective by unstaging all committed changes from a single branch and using git add --patch command to divide the work.

Tip: When you have large code reviews, it can be a great practice exercise that I also sometimes use in my workshops

to break up large code changes with this technique in retrospective.

Note, though, that it is an error-prone and daunting task to manually separate the changes.

till, you can learn a lot about single code coherence, the single responsibility principle, and your habit of mingling and tangling unrelated changes together.

Finally, git add patch is a wonderful tool when you are dealing with relatively small and local changes that you want to separate. I use it on a regular basis. And the new git command --update-refs is also helpful to synch changes between branches.

This blog post describes this technique when working with the Phabricator code review tool.

On StackOverflow, several people discuss how to generate dependent pull requests, and there are a couple of good suggestions on how to overcome this limitation in GitHub.

Over the last few years, also tools appeared that automate or assist with the creation of dedicated review branches. One of the most sophisticated ones is Graphite. Also several open source CLI tools emerged, such as ghStack, git town, or Spr.

BTW, next to my code review workshops, I also run a newsletter providing you with awesome code review tips every other week. If that sounds interesting, get your bi-weekly dose of code review best practices below!